13b. Images and Stories (continued)

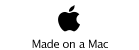

The Fighter

This illustration depicts a figure in one of my dreams. He was a hefty man in the process of punching me. His intention was to knock me out. His demeanour was fierce and determined. I was repulsed by him. At the time I was having these nightmares, I felt overwhelmed by what I was experiencing. My reality by night and by day was filled with horror.

These nocturnal images were accompanied by feelings of helplessness. Very often, I would wake in the middle of such dreams. I was left with clear images of unrelenting aggression in my mind, and with feelings of devastation.

As I reflect on this image, I see that it represents my experience of cancer, at that time. It was an aggressive, seemingly unstoppable form of cancer. There was a very real prospect of losing my life to it. I felt overwhelmed and overpowered by it. I perceived the cancer at that time as being far too strong, too fierce, and too aggressive to overcome. I felt my hope for a recovery was now futile. I was both terrified and horror-stricken by its destructive effects on my body, mind and spirit.

It is significant to me that I did not sense – however great the battle or struggle – that the “enemy” in my dreams was the final victor. This might suggest that in my battle between life and death, I was not altogether convinced that I would not survive. I am also aware that this image came from my body/mind/spirit. I suspect that I am looking at a mirror image of an aspect of my own self. In this sense, the creation and creator are one. “The fighter” – ultimately – is the fighter in me.

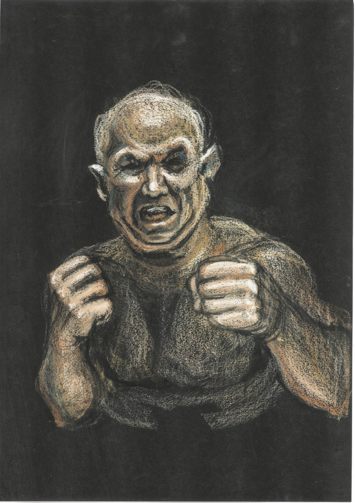

Feather Inscape

My symbol at the time was a feather. I chose the feather as my symbol after noticing that I frequently used feathers and associated images and themes in the art therapy journal I created. I used the feather as a symbol, which related to a bird. To me, it was a symbol of transcendence, which inspired larger vision and spirituality. My supervisor at the time said that there are other qualities that are also suggested by my symbol. He said that in my work as a therapist the symbol of a feather suggests that I could help clients find their lightness, their softness and their freedom of spirit.

On reflection, my supervisor’s comment was more significant than I then realised. I remember that, at that time while I was doing my art therapy degree at Master of Arts level, I was working professionally on an outreach, home-visit basis with women (mothers) with drug addiction and other major problems. It was also the end of semester at the University and I was in the process of finalising and handing in work for assessment. My combined workload was weighing heavily on me and I desperately needed a break. I imagined the kind of place I was drawn to for a holiday and this particular image came to mind – a place in the sun, close to the sea, in the stillness and beauty of sunset.

Coincidentally, the image that came to mind was also to me a landscape, equivalent to the symbol of a feather. The qualities of lightness, softness and a freedom of spirit, which my supervisor suggested were associated with the symbol of the feather, were the antithesis, the exact opposite, of how I was feeling personally at that time. While my supervisor framed the qualities of my symbol as those qualities I could offer as a therapist, they were also qualities I needed to develop and feel in myself. As I reflect on this, I now realise that the image of a feather so accurately symbolised what I most needed, what was missing for me at that point in time. These many years later, I can now see that this insight was the whole point of the exercise. I chose instinctively the symbol of the feather, which represented simultaneously certain qualities that I already possessed, as well other qualities that I needed to develop – my potential qualities, my limitations.

I recall that during times of great distress and difficulty in my life, this image has consistently come to mind. It is a comforting image, which engenders a sense of peacefulness, contentment and harmony. It occurs to me, as I look at this landscape more closely, that there is not only a consistency in the way I create this image in my mind during times of stress, but there is also a sense of familiarity and a significance about the image itself and the feeling of longing associated with it. Ultimately, I sense that this is not a created image, an imagining. It is more a memory. I am remembering my homeland, Malta, my birthplace – islands in the sun, being close to the sea, in the stillness and beauty of sunset.

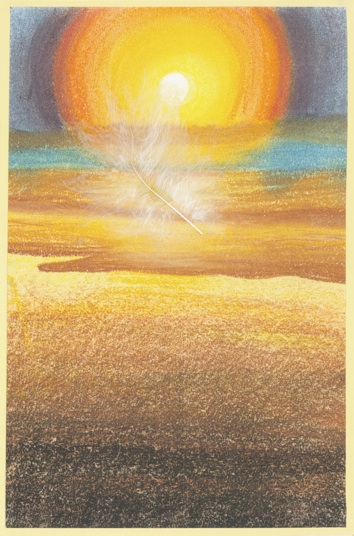

Slipping away

In the dream, we are in a small room, which is suspended high above the clouds. The room is much like a large cardboard box, the sort of thing we used to play with as children. My sisters were talking in a friendly and relaxed way. Even the one seated right on the edge of this room high in the sky was relaxed and smiling and not at all concerned about falling out. I, too, was right on the edge, but unlike my sister, I was terrified. I felt myself slipping off the edge and I was desperately trying to hang on. One of the most curious things about this situation was that neither sister was frightened, and neither sister seemed to relate to my panic. I wanted them to help – or to at least know of my predicament – but I was unable to communicate my distress. There was a strong wind that made it difficult to breathe or to speak. I also realised that from their perspective my distress was not apparent. My terror mounted as I felt myself slipping off and struggling to hold onto the sides of the room. A fall meant certain death. I awoke suddenly from the dream in a state of panic.

This dream represents my state of mind at that point in time, when I believed that death was imminent. In reality, these two sisters were at that time struggling with their own diagnosis of breast cancer. Their relaxed state of being could be interpreted as either their acceptance of their situation, their being at peace with it, or alternatively, their being unaware of the potential danger. Another possible interpretation is that they appeared relaxed, because they were, in my view, safer than I was. Their cancers were primaries, whereas mine was considered to be secondary – which meant that it had already spread. So much so, that at the time of this dream, death was a distinct possibility and the dream a true reflection of my reaction. My two sisters’ inability to see the distress I was in is related to my inability – or perhaps unwillingness – to communicate my distress.

This is reminiscent of my childhood demeanour, when it seemed futile to communicate my difficulties. As a child, I sensed that in spite of our outward behaviour (which was very different), we sisters shared the same inner experience. We shared the same sense of anxiety, injury and hardship. Today, none of my aunts or other relatives in Malta has cancer. Yet, by the time of this dream, six women in my immediate family were diagnosed with cancer – my mother, myself and four other sisters. None of my four living brothers developed cancer. On reflection, the illness was not all we women had in common. Most significantly, we had all experienced much distress – primarily the result, I believe, of having been subject to the effects of war, displacement, loss of home and country, and the pernicious effects of the aggression within patriarchal cultures on women, that is, the belief systems and behaviours, which do not truly value our existence, nor honour, respect and nurture our essentially female natures.

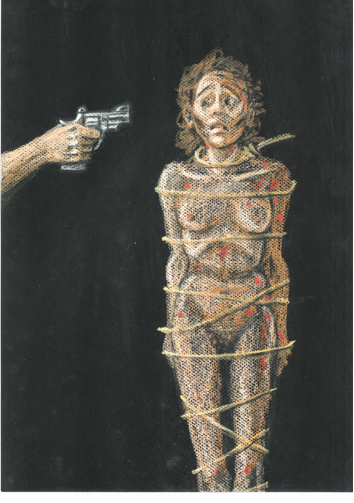

Living Horror

As I reflect on this illustration, I notice some features that reveal truths that were not drawn consciously. For instance, neither my hands nor feet are drawn. The omission of hands indicates to me the powerlessness I felt at the time; I felt unable to do anything at all about my situation. The omission of legs and feet describes my actual inability to move, to stand and to walk. I interpret the image of the gun pointing at my head as imminent and sure death. I also see it as a metaphor for the need to bring to an end my conditioned inclination to relate to my life and the world predominantly “from my head”, that is, from my thought-processes and intellect alone. There is no figure attached to the gun pointing at my head. In my mind, the figure is definitely masculine. It represents the aggressive, destructive and exploitative aspects of patriarchy.

This, for me, was ultimately a transformative and life enhancing event. I allowed myself to experience fully the feelings I had at the time – I was paralysed with fear, threatened with the real danger of losing my life, feeling extreme pain and futility. From this immersion, I noticed a sense of familiarity – I had experienced these feelings before. They were there in my childhood. I was shocked by my sudden discovery, that in spite of all my determined lifelong efforts, I had never truly transcended my childhood legacy. I had never really found the true peace of mind I had so longed for. My whole life had been one of struggle, full of effort to overcome my difficulties. At that point of realisation, I experienced profound and heart-felt compassion for myself, for the hardships I had endured, for the never-realised goal I had set for myself. I had believed wrongly that peace was something I would achieve in the future (after much hard work), however, as such, it remained in the future. This was a profound insight, one not understood merely by the intellect. It was an insight that I experienced with my whole being. I finally, profoundly, completely, understood.

This insight led to my consciously choosing a different way of being in the world. My previous focus on “doing” things (to overcome my difficulties) was clearly mistaken. My state of “being” was now paramount – a truth I had neglected unknowingly all my life, until then. Even during this very difficult and (seemingly) very late stage of my life when all seemed hopeless and futile, when I was racked with pain believing that I would not survive, I decided to live my life – however much longer it was to be – in the way I had always wanted to live it. I had believed previously that I had to struggle hard to overcome my difficulties, that I had to earn peace of mind and freedom from suffering. Everything in my culture seemed to support this delusion. I saw finally my life’s mistake clearly. I finally understood deeply – when I believed it was too late – an adage of profound wisdom and compassion: “There is no way to peace – peace is the way” (A.J. Muste).

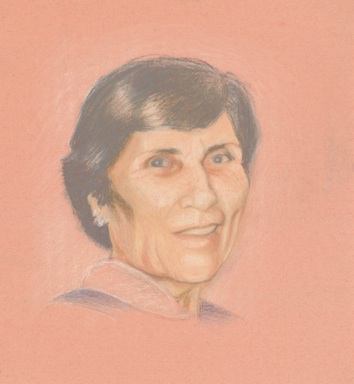

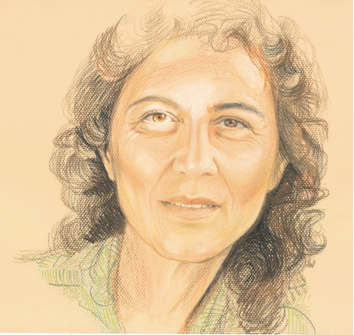

Mother

I associate this image with the very last time I saw my mother alive. She experienced a prolonged death in a nursing home. It was such a sad death, at the age of 80, after bearing thirteen children, leaving her own mother and sisters in Malta to migrate to Australia, surviving uterine cancer, the deaths of two infant and two adult children, and finally, the death of her husband, my father. I was living in Perth at the time she was dying, and I came to Sydney for a week to see her. She died a day or so after my visit, when I left again for Perth. It seemed that she had been waiting to see me to say good-bye. I remember the very last look she gave me. She was very weak and unable to move or speak at the time. The look was of profound love.

As I gazed into her face, I understood her in a way I was not able to in my younger days. It was difficult for me to communicate with my mother when I was living with my family of origin. There was so much I did not understand. My questions were often not answered satisfactorily, so I stopped asking them. I became a reticent and withdrawn child. As far as I could, I found things out for myself, and worked out my own problems. My mother belonged to another time and to another culture. There was a mismatch between her Maltese culture and the new Australian culture, which I was meant to assimilate. I learned to speak English exclusively and to go to Australian schools. At school, I was put immediately in a kindergarten school class with other “foreigners”, not in Class 2A or 2B with my Australian contemporaries, but Class 2“O”, with other immigrant children. The effect was that I did not have a sense of true belonging to either the Maltese or to the Australian culture.

My otherness, my being different, was reinforced consistently. Even when my marks earned a place in the “A” class (within a year or so), I was still ostracised and called derogatory names by other children; I was still treated with hostility and suspicion. As I look back at the context in which this was happening, I remember that it was the time of the “White Australia Policy”. I have no doubt at all that such a racist policy contributed greatly to how I was perceived by my “true” Aussie classmates. I envied their sense of belongingness and safety. I envied, too, their apparent closeness to their mothers.

The tenderness on my mother’s face at the nursing home filled instantly the gaping holes in our relationship. The awkwardness of our past relationship dissolved completely in that one look. My difficulties and anxieties all seemed to disappear. So much so, that I was inspired to look within, to discover how to look upon myself in that deeply healing way, the way I always wanted and needed to be looked at (and treated) – with such kindness, such respect, and such love.

Morphine

When morphine was first administered, I remember receiving it gratefully, as an act of mercy. At that point in time, every movement was painful, so much so, that I lay quite still. The subsequent side effects were endured necessarily: being startled awake by the inability to breathe; the deep, dark, sometimes suicidal depressions; daily panic attacks and nightmares; an inability to distinguish between wakefulness and dream states; severe constipation, and so on. The most dreadful consequence of being on morphine was my awareness of the long-term implications. The morphine was only palliative.

There was a dichotomy about my state of being during my illness. Though I looked physically weak, I was aware mentally of both my internal states and my surroundings. In fact, I was more sensitive than usual. I could perceive clearly acts of kindness. I was aware equally of acts of aversion and hostility. For example, I remember – with gratitude the care I received from a particular doctor when I was admitted into the emergency room of a public hospital, also the kindness of the doctors and nurses I encountered when I was later admitted into the Lismore hospice — these were people with whom I felt safe. This was in sharp contrast to how I felt in response to the treatment I received at a private hospital.

I arrived at the private hospital to receive radiation treatment. During that night before the procedure, I became very ill. Nurses helped Michael move me to the Accident and Emergency section. The doctor on duty refused to treat me, insisting that Michael pay the hospital fee before he would do anything at all to help. Despite the attending nurse’s protests and expressions of concern, the doctor refused to help me.

I am still stunned by the memory of this. Most of all I am shocked that a doctor was somehow able to justify such unprofessional, insensitive and unethical behaviour. I may have been unable to move and respond, but I was aware of what was happening. Panic set in as Michael saw the hospital staff stand by idly while my condition became increasingly critical.

It was this incident that led me to the realisation that within the ‘medical industry’ there is a complete area of patient care that is missing — the internal experience, such as the feeling-reality induced by morphine, is not acknowledged as real. I could not move or speak but I was totally aware of everything that was happening around me — what was happening around me had a direct affect on my ability to deal with my illness. The doctor who refused to help me frightened me and this was detrimental to my health — I could feel it.

Sometimes unexpected things can help. A little gift given to me by my sisters assumed great significance; I clung to it, I used it as a lifebuoy.

This self-portrait shows a hint of a turquoise blue pendant, which one of my sisters gave me to wear. The pendant depicts an image of the Madonna and was said to contain miraculous water from Lourdes. While I instinctively understood my sister’s (and other people’s) need to inspire hope in me, at that time, it was very difficult for me to maintain any religious belief or faith. The pain and suffering were overwhelming and unrelenting. At the same time, I had a constant, urgent need to sleep. In terms of the conventional understanding of God, I felt a sense of complete and utter abandonment. The pendant was nevertheless important; it spoke to me of my sister’s love.

If a powerful, benevolent and healing force does exist in this universe, it became apparent in the kind and loving actions of those family members, friends and strangers, who did not turn away from me during this most painful and desolate time in my life. I remember the people, who visited from near and far, the unexpected gift of money to help pay my medical expenses, the home-cooked meals and boxes of fresh home-grown vegetables that arrived at the door-step, those who held my hand, those who held me in their hearts and in their prayers, and the warm, encouraging smiles on faces known and unknown to me. Some of these people, who offered their help and support during this time, had religious or professional affiliations, and some did not.

Michael was my most constant and dependable companion. To this day, I am in awe of his courage and loyalty. I can barely understand how he made the decision to stay, and how he kept making that decision – from one catastrophe to another, from one day to another, from month to month, and as it turned out, from year to year. It is hard to imagine how he was able to endure and to survive the ordeal, given his almost total isolation, and the length and seriousness of my illness, with its huge physical and emotional demands.

I can now understand how others can abandon their partners, family members and friends in similar circumstances. I believe it is essentially a matter of self-preservation. From my perspective, Michael and those who are able to stay in the midst of “the molten chaos” and the “living grief” of a beloved’s dying, do so from a place of selflessness, one of unconditional love and compassion.

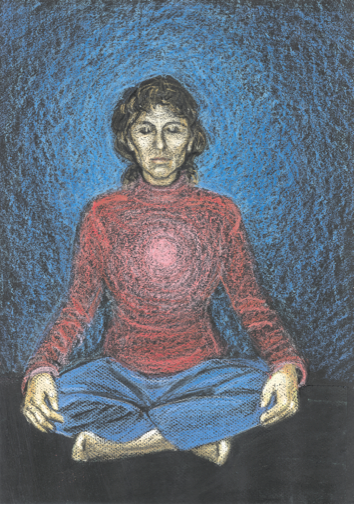

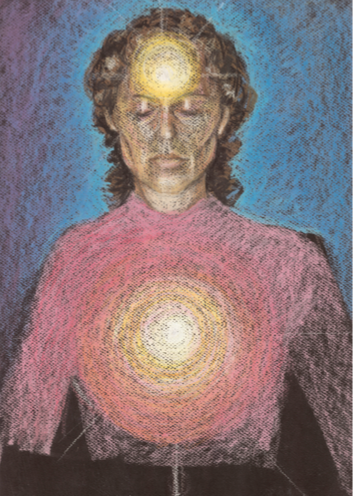

Heart of Peace

Instead, I assumed a posture in my mind, a mental attitude I adopted to cultivate the feeling of peacefulness within. This was extremely important to me, because my life had become the lived experience of horror, pain, exhaustion, of grief and utter misery. I needed to counteract this overwhelming aspect of my reality with a practice that enabled me to transcend my physical and psychological reality. At any given time, I would close my eyes and breathe in health and well-being, and breathe out weariness, distress and disease. My attention turned inward toward my heart chakra (energy field), and I focused on radiating a feeling of loving kindness towards my physical body.

In the first illustration, the radiation of loving kindness is depicted in pink, a colour associated with unconditional love. The colours of the clothes I am wearing in the illustration are colours I wear normally at home. The clothes suggest the need for protection and safety. I chose a deep velvety blue for the colour around my head. It was the first ball of colour I saw when I first began to see auras, perhaps the colour I most resonated with at the time. The blue was dark and a beautiful, soft, luminous colour.

In the second illustration, both heart and head are illuminated. I learned from the insight into my need for true peace, that the concept “peace of mind” is an inadequate one. The concept “peace of mind” maintains effectively a separation between mind and body. My previous efforts to create and develop peace of mind, ignored the needs and feelings within the body. On reflection, I believe a major cause of my illness was that emotional distress was being dealt with on a physiological, rather than on a psychological level. I now view the state of peace as both physiological as well as psychological (physical as well as of the psyche). The feeling depicted in both illustrations is one of stillness and centeredness. It is a core of peace in the eye of the storm.

Withdrawing / Emerging

When I was in the hospice and for some months afterwards, I was confined mostly to my bed, on which I lay quite still. My wanting to return home from the hospice was seen as an opportunity to grant my last request. I was told by my doctor in response to my inquiries that I could expect that my levels of medication would continue to increase until my death. However, contrary to all expectations, I very gradually became able to sit up independently, and then for increasingly longer periods of time. On discovering this hint of improvement in my health, I decided to begin to withdraw my medications, initially from the anxiety and sleeping tablets, then incrementally all the others. At that time, the medications I was taking included: morphine tablets (MS Contin for pain), a morphine liquid mixture (Ordine for “breakthrough” pain), paracetamol (Panamax for pain), docusate sodium and senna (Coloxyl with Senna laxative), Macrogol 3350 (Movicol sachet laxatives), metoxlopramide tablets (Pramin for nausea), omeprazole (Lozec Acimax to reduce acid secretion in the stomach), Temazepam (to assist with sleep), Diazepam (to assist with anxiety), chlorpromazine (Largactyl, a major tranquilliser and neuroplegic), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Celepram anti-depressant) and a bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid, Zometa). I withdrew from the minor drugs as soon as I felt I could, and I withdrew from the major drugs one at a time.

For example, I withdrew from 100 milligrams of morphine, morning and night, at an average rate of 10 milligrams per month. On two occasions, I needed to go back on to my previous dosage. On reflection, these were times of added stress. I became aware gradually of the fact that environmentally induced stress had a profoundly negative effect on me. I believe that this was because I was already dealing with an enormous amount of distress from being critically ill. Even those situations that were anticipated as pleasurable were sometimes experienced as stressful, as for example, when family or friends stayed over. My daily need for peace and quiet had become extremely important to me, and major disruptions to my routine affected me negatively. Over time, I learned to become aware of my physical and emotional needs and limitations, and to avoid or minimise any form of stress. When I perceived any physical or emotional distress, I would then wait until I had regained peace of mind and body, before continuing with my withdrawal process.

In terms of the morphine, I had the advantage of knowing that withdrawing from opiates is a physically painful process. I had worked as a drug addiction counsellor for some years and I had learned this from my heroin-dependent clients. When I consequently felt the pain of withdrawal, I knew it was to be expected. The challenge for me was to discern whether it was, in fact, the pain from malignant tumours. I judged this by noting the location of the pain. I reasoned that if it was tumour pain, it would be felt in those places I knew the tumours to be, especially the largest of them. I found this not to be the case, and so I felt the confidence to proceed.

It took about a year to withdraw totally from the morphine, then I began withdrawing from the anti-depressant, and so on, until I finally discontinued the last drug, Zometa, which was administered intravenously on a monthly basis.

In medical terms, Zometa is a bisphosphonate, an anti-resorptive agent used in the treatment of metabolic bone diseases – such as in my case, tumour-associated hypercalcaemia. My understanding of this terminology is that this drug stops the tumours from leaching calcium from the bones into the blood stream (which is a toxic condition, fatal if left unattended); this drug also stops the bones from regenerating, and thus inhibits the further growth of malignant tumours in the bone. Like morphine, the bisphosphonate was not curative, it was only palliative. My withdrawal from the drugs in general was a slow and gradual process. The outcome – unknown to me at the start – was to be my total and successful withdrawal from all the medication.

The withdrawal process was a self-managed process, guided largely by my intuition. This was not the first time I acted on insights about my health, and I had learned from painful experience not to ignore them. For me, following my intuition about my health was about obeying messages from my body. I had the distinct impression that I was getting better, in spite of my medical prognosis. When I first felt the inclination to withdraw from medications, I encountered strong opposition from my doctors and nurses. I remember their expressions of surprise and puzzlement when I made decisions that did not conform to what they believed was true about my state of health. I was actually accused of being “in denial” by those people, who were convinced that I was doomed. I sensed that they truly believed in my “terminal” status, the hopelessness of my condition, and the efficacy of the drugs I was taking. Nevertheless, I was determined to proceed.

I acknowledge that the drugs were effective, but they also had dreadful side-effects. Some of the medications, like the morphine and the bisphosphonate (Zometa), had side-effects, which were ultimately fatal at the doses I was prescribed them. I was aware from the knowledge that I had gained from witnessing my two sisters’ deaths and from doing my own research, that death from morphine would mean a sure decline that ended with asphyxiation; and that death from the bisphosphonate would be preceded by multiple bone fractures and/or necrosis of the jaw, with all the horrors of the disfiguring and often unsuccessful surgery that would result. It was difficult, perhaps impossible, to convey the reality of my terrible dilemma (death from malignant tumours or death from medical treatments) to people, medical or otherwise, who had not had the lived experience. This was a hellish time, one of interminable suffering; yet there eventually came an unexpected development, a solution to my dilemma. Though it may have seemed absurd to others at the time, I felt, I knew, ultimately I decided that I would regain vibrant good health.

In this self-portrait, I chose instinctively a light, bright coloured paper, on which to render the image, as opposed to the black paper, on which I rendered images of the dark and traumatic times of the past. This conveys the contrast between my state of being at the present time and that of past times in the hospice and for many months afterwards. In this illustration, the light colour of the paper comes through in the face. This suggests that the light is not merely surrounding me and thus produced strictly from an outside source. It emanates from within, reflecting a lightness of spirit, not previously felt.

******

Michael: Carmen began work on her doctorate soon after leaving the hospice, even before she could properly take care of herself. Carmen began work on her doctorate soon after leaving the hospice, even before she could properly take care of herself. Because it hurt when she leant forward, I constructed an artist’s easel for her that stood vertically upright. We bought a laptop computer because sitting at the desktop was uncomfortable. Sometimes she was so exhausted I had to carry her to bed. It was a full year before she was really well again.

A mundane happening brought me great joy. I came home one day and she was vacuum-cleaning the house. I danced my happiness and she laughed and laughed at my craziness. A simple little household chore was, for me, a signal on the road to her recovery. It’s astonishing, really, how important it is just to be normal, to be able to do ordinary mundane things like walking or sitting comfortably or cooking a meal. We became lovers again, and that was momentous. “I thought it might never happen again,” she said. “I believed I had lost the capacity to feel pleasure in my body.”

During the following years I became markedly sensate — she drew me into her feeling self, pleasure and pain; I experienced with her, as she created her artwork and in the process re-experienced herself, a tumultuous spectrum of emotions. She was truly, remarkable alive to the physical world.

The picture she made, depicting herself heavily sedated with morphine, was precisely how she appeared at that time — how could she have known she looked like that? Because she felt like that? The picture ‘Morphine’ is instructive — it might be shown to nurses, doctors oncologists with a caption: This is how it Feels!

Carmen’s thesis was presented for examination. One of her examiners observed:

‘There is a truth in her work that is what the very best of scholarship aims to achieve and my belief is that this truth is elegant and simple. Not simplistic — it stands as it is. And that everyone understands this form of text. It speaks to them because the person has discovered where their voice comes from and what it is that they need and want to say. They have allowed their life force to work over the interests and concerns and ideas they have upheld and this is what is shared....’

The last image Carmen made is the one I treasure most. I repeat what Carmen says of it: ‘This suggests that the light is not merely surrounding me and thus produced strictly from an outside source. It emanates from within, reflecting a lightness of spirit, not previously felt.’ There is strength, beauty and peace in this image.

Carmen came to possess a kind of numinosity that I cannot describe. Words are poor things.

Some things cannot be described or explained. I’ve learned a great deal about this from the writer and thinker Wendell Berry. When I look at Carmen’s image in ‘Withdrawing / Emerging’ I am reminded of what Wendell wrote in his essay ‘Life is a Miracle’:

“What can’t be explained? I don’t think creatures can be explained. I don’t think lives can be explained. What we know about creatures and lives must be pictured or told or sung or danced. And I don’t think pictures or stories or songs or dances can be explained.”

What Carmen created out of her life, that affected so many people, defies description and explanation in the ordinary sense. For instance, I cannot describe (with my poor words) the hope born of sorrow emerging in Henryk Gorecki’s 3rd symphony. Nor should I try. I remember what Carmen said as she was finishing her last painting: “In the year that has passed I think I have lived a whole other lifetime. It is a life that cannot be measured by minutes, or months or years; its value is momentary, a single resounding and triumphant trumpet call.”

******